Ethan Fenner, Horticulturist

A visit to the Southern African collection is rewarding any day of the year. Walking south along the main road, just past the Arid House, you’ll find the sloped beds representing an ecoregion known, generally, as “Karoo.” Derived from a KhoeKhoegowab word meaning “Land of thirst” (1), the Karoo beds are home to plants from South Africa’s western coast and inland deserts, flora especially adapted to long periods of drought.

Summer is a good opportunity to observe the succulents scattered among the rocks. Some are obvious – The fan aloe (Kumara plicatilis), for example. Others, like the small mesemb Bijlia tugwelliae, resemble the surrounding gravel more closely than any recognizable plant. And yet, some labels – a lot of labels – have no plants at all. In fact, for a Botanical Garden, there seems to be a conspicuous absence of vegetation… “It’s like a plant GRAVEYARD over here!” remarked one young, opinionated visitor.

Well, not quite. With the first winter rains come a delicate carpet of bright new leaves.These belong to the annual daisies and geophytes – plants with underground storage organs, such as bulbs or corms. Geophytes are expert opportunists, often living dormant underground for years until the right moment presents itself. It’s a strategy that has evolved multiple times in the plant kingdom all around the globe. In South Africa, geophytes lay in wait until seasonal rains arrive or a wildfire clears out the above-ground competition. In a few months, these tiny plants grow all the leaves and flowers they’ve got for that year. Then, as the rains begin to abate, the geophytes transfer energy from leaves into their underground storage banks, safe from the desiccating South African sun. They’ll shelter in place until next winter, when conditions cue the end of dormancy.

Visit the Karoo beds again in March, and you’ll find a vibrant tapestry of color. The most prevalent plants in the composition are the hybrid offspring of the geophyte Babiana plicatilis, in the Iris family Iridaceae, which fill every available crack with rich blues and purples. Except in cases of global pandemic, this yearly bloom event is not to be missed.

I’d like to turn your attention to another Babiana species that you might have missed: Babiana ringens, sometimes called the “rot stert” (rat’s tail) Babiana (2). This species is patchily distributed along the sandy soils of the western coast of South Africa in an endangered dune ecosystem called the Strandveld Succulent Karoo (3). The range extends into the Fynbos ecoregion to the south, and a subspecies (B. ringens subsp. australis) has been found on the southern coast. Growing to a maximum height of about one foot, the species is adapted to the winter rainfall, summer drought cycle typical of the Mediterranean climate.

So… what is going on with this plant? The most unusual component, by far, is the thick grey “rat’s tail” that rises above the flowers. Morphologically speaking, this is a modified flower stalk. A close inspection at the apex will reveal a few vestigial appendages where the ancestor of Babiana ringens once held flowers. But what is its purpose? Plants, especially those with short growing seasons, don’t have the luxury of wasting energy and materials on something that doesn’t aid in growth or reproduction. Extraneous appendages are weeded out over millions of years of evolutionary trial and error.

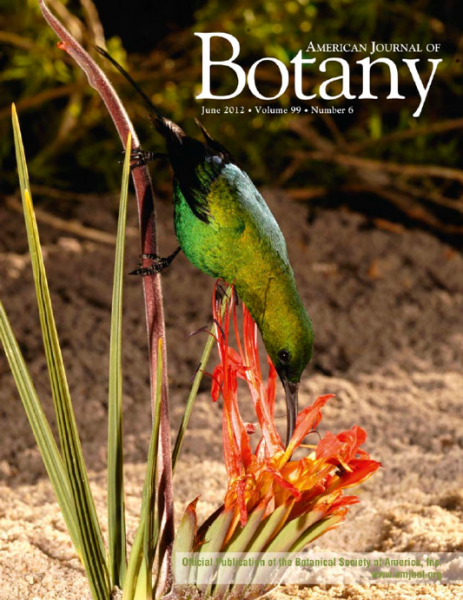

One clue is the color of the flowers. There are about 90 described species in the genus Babiana, most of these with flowers that range from blue to purple to white. These species are pollinated by different species of bee, fly, beetle, and moth (3). Babiana ringens, with its bright red flowers, is designed to attract the attention of birds, not insects (most of whom can’t see red). The malachite sunbird (Nectarinia famosa), specifically, is a nectar-feeding bird that serves as this plant’s main customer. As the pictures below illustrate, the “tail” is actually a perch, perfectly positioned for a malachite sunbird to stick its face down into the nectar-rich flowers, inadvertently making contact with the ascending stamen and pistils. The malachite sunbird, now with a chest full of pollen, continues its search for nectar by probing the other flowers nearby. While bird pollination in itself is nothing unusual, the remarkable fact about Babiana ringens is that it has to regrow a perch sturdy enough for a sunbird every single year.

A male malachite sunbird (Nectarinia famosa) probing the flowers of Babiana ringens. As the beak reaches in for the nectar, the chest makes contact with the stamen and pistils. Photo credit: de Waal, Barrett, Anderson (2012).

How well does this perch actually work? Botanists performed a simple field experiment where they removed the perches from half of the plants, and kept the other half of the plants intact. While removing the perch didn’t affect the development of the flowers, it certainly influenced how attractive the plants were to the malachite sunbirds. Plants without a perch were visited about half as frequently, and birds spent less time investigating the percheless flowers. Without the perch, the sunbird is forced to land on the ground and approach the flowers from the side. Doing so means they are much less likely to come into contact with pollen on the upward-facing anthers, and less likely to transfer that pollen to the upward-facing pistils. Compared to unmanipulated plants, flowers without a perch produced 47% fewer seeds and had significantly reduced levels of cross-pollination (4).

So the perch is important. Not only does it seem to attract more sunbirds, but it manipulates them into the perfect position for efficient pollination: Beak down, tail up. I’m not a sunbird – but to me that seems like an uncomfortable way to eat lunch. If a plant is going to all the effort to grow a perch every year, why would its flowers be in such an inconvenient spot? Other Babiana species, even those that are bird-pollinated, have flowers higher above the ground – usually a better way to get noticed by birds.

There are a few last pieces to the puzzle. Botanists compared Babiana ringens with its closest living relative: Babiana hirsuta. This species also has red flowers, is also pollinated by sunbirds, and is also endemic to the sandy soils of the western coast of South Africa. But while Babiana ringens only flowers at the ground, Babiana hirsuta has multiple side branches all the way up and down the stalk. Researchers noticed that grazing herbivores damaged Babiana hirsuta much more than Babiana ringens. In both species, the tops of plants were chewed off much more than the bottoms. Field experiments suggested that if Babiana ringens had flowers at the top of the stalk instead of the bottom, it would very likely suffer much more damage from herbivores and produce less seed (5). When you live in nutrient poor environments, and you’ve only got one shot a year to make seeds, you’re wise to keep your flowers as safe as possible.

Babiana ringens has found an interesting and beautiful way to survive and reproduce in a less forgiving environment. Next March, keep an eye out for this species in the Southern African Collection, Bed 130.

Works cited and links to further reading

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. Karoo (last updated 2019). Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc. https://www.britannica.com/place/Karoo

The Editors of The Pacific Bulb Society. Babiana Four (last updated 2019). https://www.pacificbulbsociety.org/pbswiki/index.php/BabianaFour#ringens

de Waal, C., Aderson, B., Barrett, S. (2012). The natural history of pollination and mating in bird-pollinated Babiana (Iridaceae). Botany, 109: 667-679 http://labs.eeb.utoronto.ca/BarrettLab/pdf/De%20Waal%20et%20al%20(2012)%20AofB%20Babiana%20pollination.pdf\

Anderson, B., Cole, W., Barrett, S. (2005). Specialized bird perch aids cross-pollination. Nature, 435: 41 https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Bruce_Anderson3/publication/7865557_Botany_Specialized_bird_perch_aids_cross-pollination/links/00463516d6f3791dca000000.pdf

de Waal, C., Barrett, S., Aderson, B. (2012). The effect of mammalian herbivory on inflorescence architecture in ornithophilous Babiana (Iridaceae): Implications for the evolution of a bird perch. American Journal of Botany, 99: 1096-1103. https://bsapubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.3732/ajb.1100295