Image above: A selection of cones from a variety of conifers

Dr. Lew Feldman, Garden Director

Cones, such as found on pine trees, serve to protect the developing seed. Sometimes too, pine cones function in dispersal of the seeds. Because of their often large sizes, it takes a lot of energy (photosynthate) to make a pine cone. Thus, if there were no seeds inside, it would be wasteful for the plant to expend energy to make large cones. So how does the plant “decide” whether to make a cone?

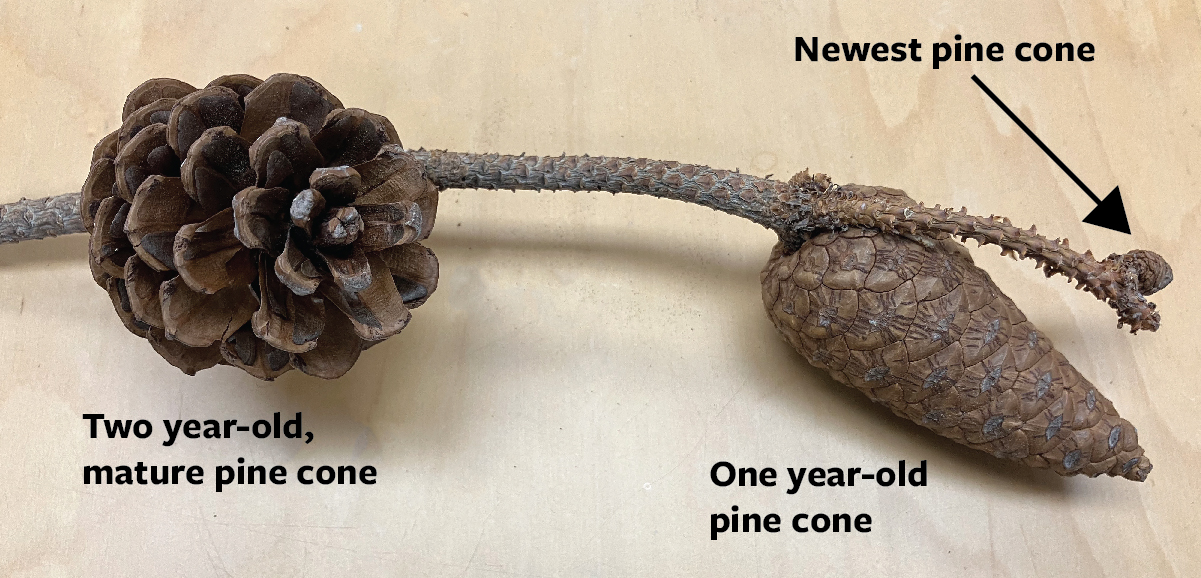

As you walk through the California section of the UC Botanical Garden have a look at the branches of cone bearing trees, such as the Ponderosa Pine, (Pinus ponderosa). If the branch is low enough you will easily notice large, fully mature cones. But if you look more closely, you will observe that along the branch axis there is a series of cones, of gradually decreasing size, with the newest, youngest, and smallest cones near or at the tip of the branch. This progression of cones can be thought of as representing different years or ages, as pictured below.

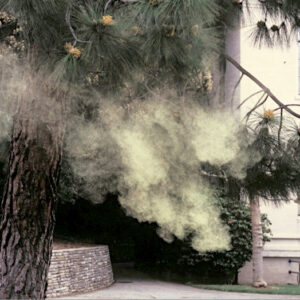

Returning now to our question of how the plant “decides” whether to make a large cone: the signal for the small cone to enlarge is pollination and fertilization. When the cone is new, and the tree has not yet put much energy into making it, the scales on the small cone open, and pollen which has been shed by other trees is carried by the wind [image below right, showing pine pollen being shed and dispersed/carried by the wind to the newest cones] to the small cones and enters through the slightly separated scales. The pollen then sifts down to the egg (the female portion) where fertilization occurs. It is the process of fertilization and the onset of seed development that is the signal for the cone to enlarge. After pollination/fertilization the scales close tightly, thereby protecting the internally developing seed.