Dr. Lew Feldman, Garden Director

In this edition of IGYA we will consider bark, which is the outermost layer of trees, woody shrubs and vines, and which can be thought of as the “skin” of a woody plant. Bark is essential for a tree’s survival.

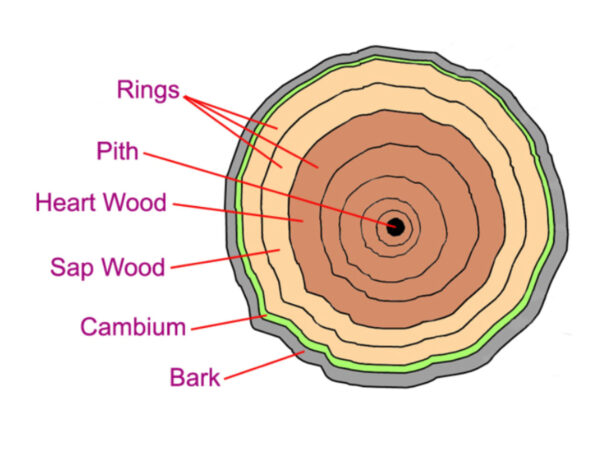

Bark has an important role in protecting the plant from environmental insults, ranging from insect attacks to damage from fires and cold, and acts as a barrier to infection. Technically, the term bark refers to all the tissues surrounding and outside of a layer of cells known as the cambium.

View of a cut across a tree trunk showing the bark and various internal tissues layers (From: Tree of Life).

And while bark mostly consists of dead cells, the region of the bark just outside of and touching the cambium is alive and has a very important function both in forming the new bark, and in moving (transporting) much of the organic materials which nourish the plant.

Bark can be composed of various different cell types, among which are cork cells. By incorporating cork as part of the bark, the tree is able to insulate and protect underlying, living cells, from fires, as are common in many wooded California grasslands (a wooded grassland has woody plants covering between 10 and 40% of the ground).

Many trees produce chemicals in their bark which fend off or prevent attack by insects and fungi. Other trees discourage such attacks by periodically shedding their bark (pictured below in Eucalyptus), thereby ridding themselves of unwanted, attached visitors.

Shedding of bark (Wikipedia)

Bark also provides a home for many species of insects and spiders. These invertebrates attract birds, such as tree creepers and crested tits.

Bark can also provide a substrate (habitat) for many other plants, collectively called epiphytes (= plants which grow on other plants), with one of the most common epiphytes being Spanish “moss” (which is actually a bromeliad, Tillandsia usneoides).

Spanish moss growing on the bark of a tree (from Island Life NC).

And, as most of us have seen, bark can also provide a habitat for many lichens.

Tree dwelling lichens (from the New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station)

But bark, as a protective barrier, can be bridged, with accompanying severe consequences for the tree. Here in California one of the most damaging insects to trees is the bark beetle whose larvae burrow through the bark into the cambium leaving behind distinctive galleries or passage ways.

Bark beetle (Scolytidae family) galleries under the bark of an elm tree. The center of the gallery is where the eggs of this insect were laid. (Riveredge Nature Center).

Larger animals can also injure trees by damaging the bark. Voles can kill young saplings by eating the bark at the base of young trees, and for some animals, such as the beaver, the bark is consumed as food, as in aspen and willow.

Humans too have also exploited bark. Products include roof shingles and building siding; and then there is the famous birch bark canoe, pictured below.

Birch bark canoe crafted by Steve Cayard (Pinterest)

Bark too is the source of the spice cinnamon, an aromatic flavoring used in a wide variety of cuisines. Stems of the cinnamon plant (Cinnamomum verum) are “processed by scraping off the outer bark, then beating the branch evenly with a hammer to loosen the inner bark, which is then pried off in long rolls. Only 0.5 mm (0.02 in) of the inner bark is used; the outer, woody portion is discarded, leaving metre-long cinnamon strips that curl into rolls (“quills”) on drying. The processed bark dries completely in four to six hours, provided it is in a well-ventilated and relatively warm environment. Once dry, the bark is cut into 5 to 10 cm (2 to 4 in) lengths for sale” (from the publication, “Source of Flavors”).

Close-up view of “raw” cinnamon (Wikipedia)

Notable health-related products from bark include aspirin [from the bark of willow (Salix) trees] and quinine, used to treat malaria (from the bark of Cinchona spp.). Quinine also flavors tonic water, giving it its bitter taste.

We end our discussion of bark by noting that many gardeners grow selected plants because of their unusual and colorful bark, as pictured below.

Stewartia pseudocamellia tree trunks (LeBeau Bamboo Nursery and Coast Explorer Magazine)