Dr. Lew Feldman, Garden Director

In this issue of IGYA we want to begin a discussion of how plants control their growth and development. In particular, I want to consider how our understanding of these controls relates to common horticultural practices.

As in animals, plants too have signaling molecules which occur in extremely low concentrations and which influence all aspects of plant development. The discovery of these molecules, at least an inkling of their existence, can be traced back to Charles Darwin. Following his observations, which he and his son published in a book, The Power of Movement in Plants, the first, certain identification of a signaling molecule occurred in the early-mid 20th century with the discovery of a compound (abbreviated as “IAA”) and given the common name of, “auxin.” Soon after the discovery of auxin, other signaling molecules were found, with the main ones being the gibberellins (abbreviated “GA”), the cytokinins and ethylene.

In this edition of IGYA we will focus on auxin.

We now know that auxin influences a wide variety of developmental events, including rooting of cuttings, development of fruits, the increase in width of trees and the shape of the plant’s body (whether branches grow out or not). Let’s consider how each of these developmental events relates to horticulture.

The shape or architecture of plants

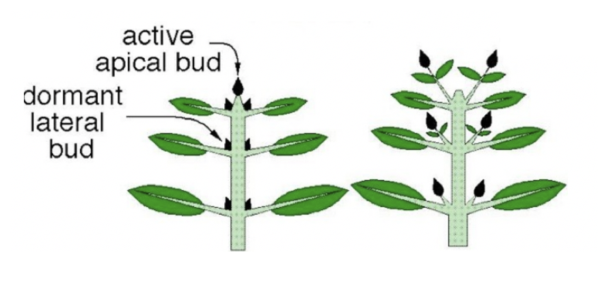

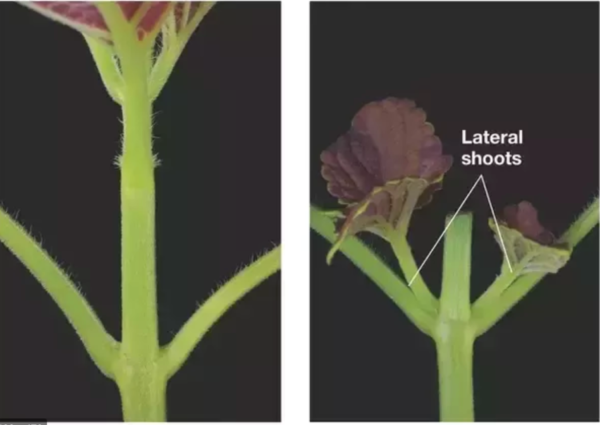

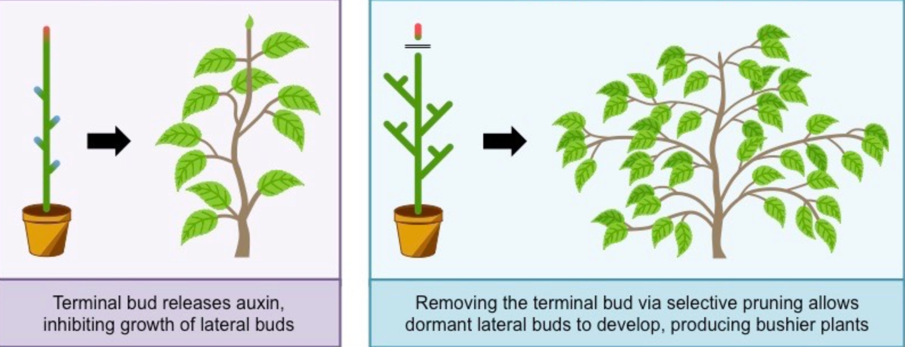

The first characteristic to know about auxin is that it is mainly produced at the very tips (the growing point) of plants and from there moves to all portions of the plant. If a plant is producing a large amount, as the auxin moves away from the tips it passes buds lower down of the stem which have not yet grown out into branches. When a bud which has not grown out is exposed to a high level of auxin coming from the tip of the plant, that bud is prevented (inhibited) from developing any further and will not grow out to form a branch. Plants producing a lot of auxin at their tips usually have a single, main axis with few or any branches, such as a palm tree. This is contrasted with a plant having many branches, in which the level of auxin throughout the plant is likely quite low, and therefore the buds can grow out. So for those of you who desire bushy plants (= lots of branches and flowers), you accomplish this by removing (“pinching” off) the tip of the plant…the main auxin supply, thereby allowing many buds to grow out.

Diagram showing the effect of removing the terminal (active apical) bud on dormant lateral buds (Simplified Biology).

Coleus plants showing nodes on an intact stem (left) and on a plant from which the main shoot tip has been removed (Pearson Benjamin Cummings).

Diagram showing the effects of removing the terminal shoot tip on plant shape (BioNinja).

Rooting of cuttings

Root formation on Cape jasmine (Gardenia jasminoides) cuttings exposed to different concentrations of auxin (IAA) (Asian Journal of Horticulture).

A common practice for the Volunteer Propagators in the Botanical Garden is to start new plants by making cuttings of the parent plant in the Garden collection. After making the cutting the lowermost end of the cutting is dipped into or brushed with a powder containing either a naturally occurring auxin or a synthetic auxin, and then the cutting is inserted into soil. Sometime later (weeks to months), the lower, powdered surface of the cutting will sport roots. Developmentally, what the applied auxin has done is to reprogram cells in the stem to grow into roots. Commercial preparations of auxin are given names to reflect this re-programming property, e.g. Rootone (which contains either naturally-occurring auxin [IAA] or a synthetic auxin).

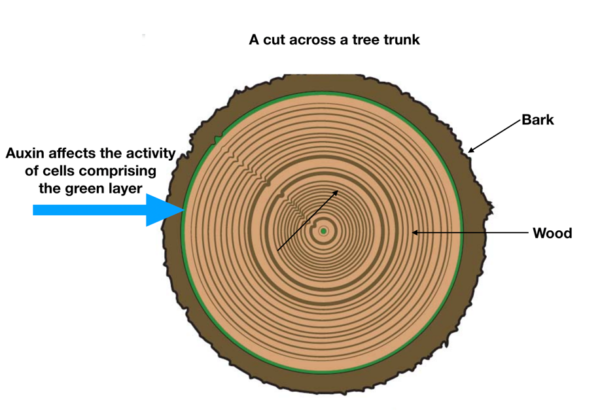

Tree width

As they grow in height, most trees also grow in width. This increase in girth can be traced to the production of new cells, from a layer of cells located inside the tree, causing the tree to widen.

The activity of this layer of cells (indicated by the green layer), that is, how quickly they contribute to widening of the trees, is, in large part regulated by auxin coming from the shoot tips. This is why if you cut off all shoot tips from a tree, it will slow down or stop increasing in width.

Fruit Development: Size and Shape

One of the most obvious characteristics of fruits is their size and shape, varying from small-sized fruits, such as blueberries, to the giant, often half-ton pumpkins displayed at Halloween. It is now known that the shape and size of fruits is largely regulated by auxin.

Blueberry fruits (Tasteofhome.com)

A prize-winning pumpkin (Park Seeds)

Big fruits make a lot of auxin. So where in the fruit is the auxin made? The answer is in the seeds. Moreover, the location of the seeds in the fruit correspond to where auxin is most highly concentrated and thus, which part of the fruit grows the most. This is the reason why pears are pear-shaped, or why butternut squash is enlarged at one end; the enlarged portion of the fruit is where the seeds are located.

Seed distribution is associated with the region of enlargement of fruits; pear (left) squash (right) (Park Seeds).

In experiments conducted over 50 years ago it was shown that if you removed the seeds from a fruit when it was very tiny, that the fruit failed to enlarge. But if you treated with auxin these tiny fruits that had had their seeds removed, they could enlarge and develop more or less normally.

Does this mean that the increasingly available number of seedless fruits in stores result from treating the small fruits with auxin? In some cases, the answer is “yes.” As gardeners living in San Francisco know it is often difficult to grow tomatoes. This is because pollen does not develop well in cool, foggy weather and hence there’s no chance for seed formation. However, if flowers of tomatoes (or eggplant or peppers) are sprayed with auxin, fruit formation can occur without seed formation.

In other instances, such as in seedless watermelons or bananas, seedless fruits can develop in one of two ways: either the fruit develops without fertilization (with another source of auxin), or alternatively, pollination itself occurs, but the tissues (embryos) that could become the mature seed, abort (these are the little “dots” you see in bananas). But in both watermelon and bananas, even though mature seeds never form, auxin is still necessary.